Corporate-Educational Complex

Published on Apr 22, 2024.

Seventy years ago, Dwight Eisenhower coined the "military-industrial complex". In his farewell speech, he warned us that a network of common interests was developing between the US military and the private sector that supplied the military with weapons. This network operated in the shadows beyond the reach of democratic oversight, with large amounts of money at their disposal. It posed the greatest threat to democracy, he warned, even more so than than the Soviet Union.

Today a new nexus of unchecked power and influence has emerged. It bears some resemblance to its military industrial predecessors, but it doesn't involve the army or defense contractors.

It is the corporate-educational complex – a combination of breeding grounds for the world's governing elite and the halls of financial power they wield through their global corporations. The two feed off each other, in a close-knit feedback loop that shapes the culture that shapes the world.

It's the job of the universities to indoctrinate new classes and new generations. It is the job of the corporations to harness a trained and complacent flock, to turn them into the ends of profit for a very select few.

If the universities are the temples, the corporations are its priests.

The link between them begins at the entry point to the corporate world. It begins at the job market.

We are trained to believe that companies hire in as fair and rigorous a way possible. Like tests in school, that we accept as fair measures of our worth, even though they are just games, we accept the processes of getting a job with just as much faith.

Getting a job at a prestigious corporation is as much a game as getting into an elite university. It pretends to be something it is not, and the kids trained at elite universities know this. They know the tricks and the way to win.

Let's start with the resume – the cornerstone of the recruiting process. Ostensibly, it's your opportunity to list in detail your accomplishments and achievements. In theory, the best case you can make for a job are the things you've done before.

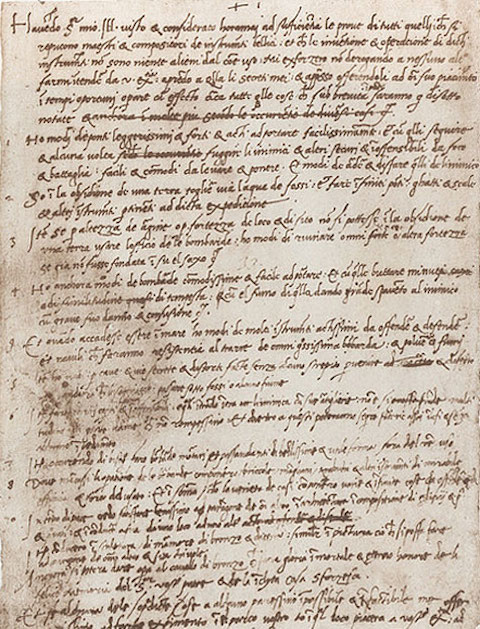

This is what Leonardo da Vinci was thinking when he invented the resume in the 1500s. At the time, he was a no-name artist in Italy and he desperately needed a job. So he drew up a list of all the things he had created – like the cannons he had built and how far they shot. This was the world's first resume, and it totaled 11 pages.

Many people still believe that's the way the resume still works today. They pour hours into it, phrasing and rephrasing and re-rephrasing the work they've done. Naively, they believe someone's actually going to read it.

But in reality, there is only one thing that matters in a resume, and those are the names. The names of the places you worked and the names of the places you went to school.

"This person worked at Google as a Senior Analyst I," they'll proclaim. Ask them what the person did, and they probably have no idea. It's just the prestige that stuck in their heads.

Prestige is our modern-day version of the sacred. An invisible aura around certain things that gives them a special sense of value.

In a special irony, most college grads try to go work at big-name corporations, even though small companies tend to be better places to learn. Small companies provide more opportunity for responsibility and they don't peg people into small, specific roles. While the big-name places, the role of any single individual is a tiny little piece of a slightly larger chunk in just one vertical in a giant machine.

But kids flock to the big names because corporations have honed a special place in our society. Their names ring with prestige. And kids are like little magnets for prestige – just like the rest of us.

Imagine I told you about a company that made a big bet on a new business which ended up failing miserably. Their competitors called them foolish when they did it and no one thought it was a good idea. But they tried to do it anyway – they sunk money and people into an unpopular idea because they thought that made them have a competitive advantage. They turned out to be wrong.

If I then told you that this company was your corner grocery store, and they tried to open a lawn equipment rental business, you'd agree that they were stupid. But if I told you the company was Goldman Sachs, and they bet on a sector of the bond market that didn't pan out, you'll probably consider them risk-taking and innovative anyway.

Our perspectives are always clouded by our prejudices. And no prejudice is as strong in our minds than the prejudice of prestige.

This is the last post on a series on colleges and education for a while. I'll take a break for a little while, before moving onto the media next.